3D Printing Just Got a ‘Muscle’ Upgrade: The End of Rigid Robots?

I still remember the first time I saw a 3D printer work. It was mesmerizing, watching layer upon layer of plastic slowly build a rigid, unmoving object. Usually, it was a little boat (Benchy) or a Yoda head. But no matter how cool it looked, it was always just a hard shell. If you wanted it to move, you had to attach motors, wires, and screws later.

Well, that era might be ending sooner than we thought.

A team of engineers at Harvard has just flipped the script. They haven’t just printed a robot; they have figured out a way to print the movement itself directly into the material.

This isn’t just an “update.” It’s a complete rethink of how we build machines. If you’ve been following the rise of Soft Robotics (robots made of flexible materials rather than metal), you know the biggest headache has always been assembly. Harvard just solved that.

Here is why this development has me so excited—and why it matters for the future of tech.

The Problem: Soft Robots are Hard to Make

Let’s be honest: building a robot that mimics biology is a nightmare.

Traditional soft robots—think of those gripper arms that can pick up an egg without breaking it—are usually made through a tedious process. You have to mold the parts, cast them, glue layers together, and pray there are no leaks. It’s slow, expensive, and prone to human error.

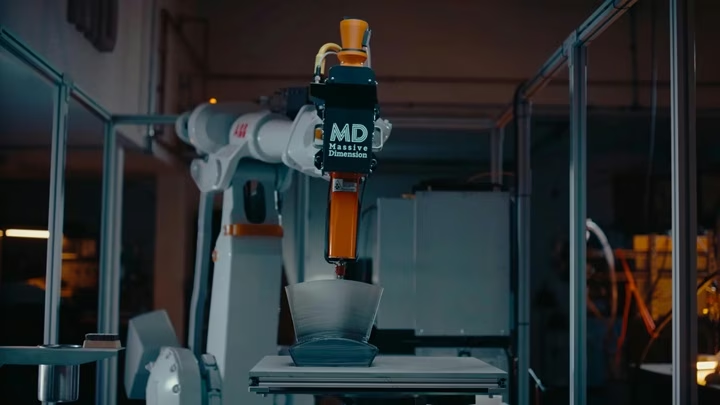

The Harvard Breakthrough: The researchers published their findings in Advanced Materials, and the core innovation is something they call “Rotational Multimaterial 3D Printing.”

Instead of printing a static shape and hoping you can animate it later, this new technique prints the body and the muscles simultaneously in a single go. No glue. No assembly. Just print and play.

How Does It Actually Work? (The “Jelly” Secret)

I dug into the technical details so you don’t have to. The genius here lies in a spinning nozzle.

Imagine a soft serve ice cream machine, but much more precise. The printer uses a rotating nozzle to deposit filaments with a specific, twisted structure. But here is the kicker: it prints two materials at once.

- The Shell: A durable, flexible outer layer (Poliüretan).

- The Core: A temporary, gel-like ink (Poloxamer).

Once the printing is done, the structure is washed. The temporary gel dissolves and washes away, leaving behind hollow, complex channels inside the solid shell.

These empty channels act like pneumatic muscles. When you pump air or fluid into them, the robot moves. But it doesn’t just expand like a balloon; it moves in a very specific, pre-calculated way.

Coding with Geometry, Not Chips

This is the part that blew my mind. Usually, if you want a robot to twist, you write code in a microcontroller.

With this new method, the geometry is the code.

By controlling the angle and spin of the nozzle during printing, the engineers dictate exactly how the robot will behave before it even exists.

- Want it to coil like a snake? Print the channels in a spiral.

- Want it to grab something? Print the channels to contract inward.

The movement is “programmable,” but the program isn’t written in Python or C++; it’s written in the physical structure of the filament itself. The team demonstrated this by printing a spiral actuator that blooms like a flower when pressurized, and a gripper that can hold objects—all printed as a single, continuous piece.

Key Takeaway: We are moving from “Hardware + Software” to “Hardware as Software.” The physical object knows what to do based on its shape.

Why This Changes the Game

You might be thinking, “Okay Ugu, cool science project, but what does it mean for me?”

The implications are actually huge, especially outside of factory floors.

1. Safer Medical Tools

Imagine surgical tools that can navigate the soft, complex curves of the human body without damaging tissue. Because these robots are printed in one piece, there are no seams to harbor bacteria, and they can be customized to a specific patient’s anatomy in hours, not weeks.

2. Wearable Tech that Actually Fits

We’ve all tried “ergonomic” gear that wasn’t actually ergonomic. This tech could lead to exoskeletons or support braces that mimic human muscle structure exactly, providing support without restricting movement.

3. Rapid Prototyping

For inventors and makers, this cuts the development cycle from days to hours. If you don’t like how the robot moves, you don’t need to re-assemble it. You just change a few parameters in the print file and hit “Print” again.

My Final Thoughts

I often write about AI and digital metaverses, but we can’t forget that the physical world is catching up.

We are seeing a convergence where biology is inspiring engineering. We aren’t trying to build metal men anymore; we are trying to build synthetic organisms. This Harvard study is a massive step toward robots that feel less like machines and more like… well, us.

It’s efficient, it’s elegant, and it removes the most annoying part of robotics (the assembly).

I’m curious to hear your take: If you could 3D print a robot helper for your home tomorrow, would you trust a “soft” robot to handle your fragile chores (like doing the dishes), or do you still prefer the precision of rigid metal machines?

Let’s chat in the comments!